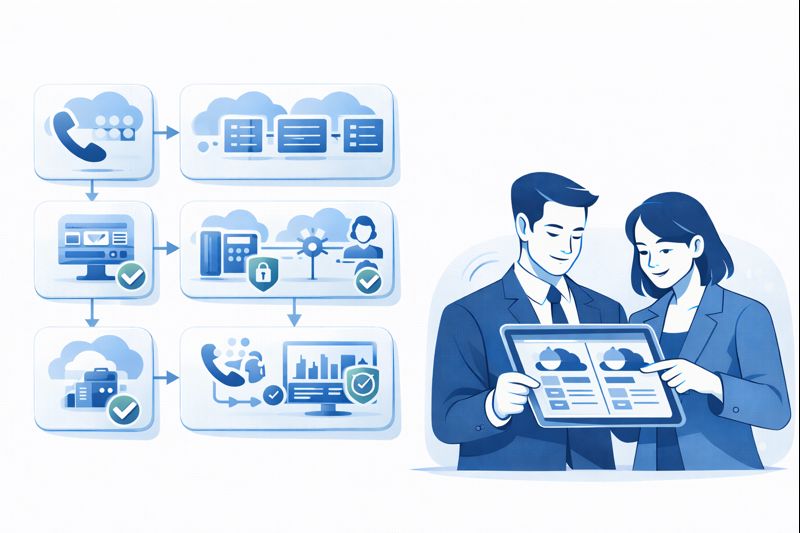

To a customer, pressing “Call” feels simple: tap a button, hear a ring, speak to a human. Underneath, dozens of systems negotiate codecs, routes, permissions, data, and fallbacks in milliseconds. If you don’t understand that hidden architecture, you end up blaming agents for problems created by trunks, SBCs, IVR flows, or routing rules. This guide walks through what actually happens from the moment a customer hits “Call” until the interaction is wrapped, recorded, and analysed — so you can design a stack that feels instant, reliable, and intelligent instead of fragile and mysterious.

1. The First 500 Milliseconds: From Mobile Network to Your Edge

As soon as the customer presses “Call,” their device hands control to the mobile or fixed-line carrier. The call is encoded (G.711, G.729, Opus, etc.) and routed across the public network toward the number you’ve published. If you’re using SIP trunks, the carrier will hand off traffic to your SIP endpoint, often protected by a Session Border Controller (SBC). That SBC is your front door: it validates signalling, enforces security policies, and routes calls into your cloud PBX and VoIP layer so one global number plan can fan out across queues, locations, and devices.

Any jitter, latency, or packet loss at this stage already shapes perceived quality. Cheap or misconfigured trunks can introduce problems your agents can’t fix. This is why carrier choice, peering, and SBC configuration belong in board-level architecture conversations, not just “IT plumbing.”

2. Cloud PBX, SIP, and Number Translation: Where the Call Actually Lands

Once the call hits your SBC, the cloud PBX translates what the carrier thinks it’s delivering (a specific DID) into internal routing logic. Here you decide whether a number is tied to a main IVR, a campaign, a country, or a VIP hotline. Good implementations separate numbering from logic: you can change IVR flows or queues without renumbering everything, the way modern cloud contact center platforms do.

At this stage, the architecture also decides what to do if your primary region fails. Do calls overflow to a second data center or cloud region? Do they fail over to backup carriers? Architectures that treat PBX, trunks, and routing as one mesh can sustain incidents without customers ever knowing something broke.

3. IVR, DNIS, and Entry Flows: The First Experience Layer

After number translation, the call is pushed into an IVR or auto-attendant flow. Caller ID, DNIS (the number dialed), and sometimes geo data inform which tree the customer hits. A banking customer calling from a known device may get a different menu than a new prospect dialing your sales line. Smart IVR design acts as a pre-router, not just a voice menu, similar to the way modern cloud call center architectures unify flows across channels.

This is also where you decide whether to authenticate, identify intent, or offer callbacks. Every additional menu layer adds time and risk of abandonment. Architecturally, IVR flows should be versioned, observable, and easy to roll back if they damage KPIs. Hard-coded menus buried in legacy systems are a common reason changes take months instead of days.

| Layer | Primary Purpose | Primary Owner | Common Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carrier Network | Connect caller to SIP trunk / DID | Telecom / Network | Latency, routing congestion, regional outages |

| SIP Trunks | Deliver calls into SBC/PBX | Telecom Lead | Codec mismatch, poor capacity planning, misrouted numbers |

| Session Border Controller | Security, signalling, edge routing | Voice Network Team | Overloaded CPU, misconfigured rules, no geo-redundancy |

| Cloud PBX | Number plans, hunt groups, basic features | UC / Telephony | Legacy dial plans, brittle configs, slow change cycles |

| IVR / Entry Flow | Gather intent, route to right queues | CX + Telephony | Over-complex menus, low containment, high abandonment |

| Routing Engine / ACD | Queue selection, agent matching, SLAs | Contact Center Ops | Static rules, no skills tuning, SLA breaches |

| CTI / Desktop | Deliver call controls + context to agents | Apps / CC Tech | Slow screen pops, desynchronised data, crashes |

| CRM / Ticketing | Customer records, cases, interactions | CRM / CX Tech | Duplicate records, poor linking to calls, manual logging |

| Recording & Storage | Store audio, screens, transcripts | Compliance + Voice | Gaps in recordings, retention issues, non-compliant storage |

| AI / Transcription | Turn speech into searchable text & signals | AI / Data Team | Low accuracy, language gaps, missing integrations |

| QA & Coaching | Score interactions, improve behaviour | QA Lead | 1% sampling, manual bias, delayed feedback |

| Analytics & BI | KPI trends, root-cause, forecasting inputs | Analytics / COO Office | Fragmented data, mismatched definitions, slow queries |

| WFM | Forecast volume, schedule staff | WFM Team | Bad forecasts, no intraday management, manual updates |

| Reporting to Leadership | Summarise health, risk, opportunities | COO / CX Head | Vanity metrics, no linkage to architecture realities |

| Resilience & DR | Failover, continuity, disaster recovery | IT + Ops | Un-tested runbooks, single-region design, unmonitored backups |

| Security & Compliance | Data protection, access control, audits | Security / Compliance | Over-permissive access, weak audit trails, unclear ownership |

4. Routing Engine and ACD: How the Call Finds an Agent

Once the IVR captures intent (explicitly via menu choice or implicitly via number and history), the routing engine and ACD decide which queue and which agent should get the call. Basic setups route on longest idle or simple skills; advanced setups consider language, value, compliance requirements, and predicted handle time. This is where architectures using predictive routing models pull ahead: they use historical outcomes to place the right calls with the right agents, not just the next free seat.

Architecturally, routing should be abstracted from the dial plan. You want the freedom to spin up new queues, overflow paths, or VIP lanes without touching trunk configs. Routing rules must also be observable: you need to see when a misconfigured failover is sending high-value traffic into generic queues.

5. CTI, Screen Pops, and CRM: When Audio Meets Data

As the call is ringing on the agent’s side, the CTI layer fires. It matches caller ID, IVR path, and any known identifiers against CRM or ticketing records, then pushes a “screen pop” to the agent desktop. Well-designed CTI exposes exactly what the agent needs in the first three seconds: who this is, what they last did, and why they might be calling, the way strong integration-first call center stacks do.

If the CTI and CRM are poorly integrated, agents see blank screens, duplicate profiles, or outdated information. That pushes them into manual search, extends handle time, and makes your carefully-built routing logic pointless. This layer is also where embedded call controls live, so agents can handle calls without juggling windows. Architecture decisions around single-pane-of-glass vs multiple apps show up in every second of handle time.

6. Recording, Encryption, and Compliance: What Happens to the Media

By the time the customer says “hello,” the architecture has already decided whether to record, where to store, and how to encrypt that audio. Some regions and industries require dual-consent announcements; others require selective recording (e.g., pause during payment capture). Modern stacks tag recordings with rich metadata so you can retrieve “all calls about card fraud from KSA last week,” aligning with the patterns used in call recording compliance frameworks.

Architecturally, you want recording to be centralised, not scattered. If different platforms record different slices of the interaction, audits and investigations become nightmares. Retention policies, encryption keys, and access controls must be managed like financial systems, not “nice-to-have logs.”

7. AI, QA, and Analytics: Turning Conversations into Architecture Feedback

Every call throws off data: audio, transcript, sentiment, handle time, hold patterns, outcomes. In a legacy architecture, 1–2% of calls are sampled by QA and the rest vanish. In a modern stack, AI listens to 100% of calls, transcribes them, and scores behaviour against your playbooks, similar to what’s described in AI-driven full coverage QA.

This isn’t just about agent coaching. When you aggregate QA and AI signals, you see which IVR branches generate repeat calls, which queues suffer from misrouting, and which regions have connectivity issues. Architecture should feed analytics, and analytics should feed architecture: routing rules, carrier choices, IVR prompts, and AI assist models all evolve based on what conversations reveal.

8. Cloud vs Legacy: How Architecture Changes the Same Call

Take the same customer, the same number, and the same intent — their experience will differ massively depending on whether you’re running modern cloud infrastructure or a patched legacy ACD. In cloud-native designs, calls land in elastic compute, routing rules can be changed in hours, and new channels plug into the same backbone, like you see in UCaaS + CCaaS unified stacks.

In legacy designs, any change to IVR, routing, or capacity might require hardware upgrades, maintenance windows, and vendor PS projects. Disaster recovery tends to mean “fallback to voicemail,” not “seamless failover to another region.” Architecturally, the question is no longer cloud vs on-prem as a buzzword; it’s whether your design allows you to respond to business and regulatory change at the pace your customers expect.

9. Uptime and Resilience: Designing for 99.99% and Beyond

The architecture behind 99.99% uptime is not magic; it’s a chain of deliberate decisions. Multi-region call handling, redundant carriers, stateless routing services, and active-active failover add complexity, but they’re the reason some operations barely blink during outages. This is the mindset behind modern low-downtime contact center infrastructure.

At the blueprint level, you should know exactly what happens if: one carrier fails, one region dies, one database cluster goes read-only, or one CRM becomes unavailable. Does the system gracefully degrade (e.g., fewer screen pops, still routing), or does it drop calls? Run game-days where you simulate these failures and prove the architecture behaves the way diagrams promise.

10. Metrics as Architecture Feedback: What to Watch

Many teams stare at AHT, ASA, and abandonment without tracing them back to architecture. A more powerful approach uses metrics as design feedback, like the best-practice patterns laid out in call center efficiency benchmark playbooks. For example, sudden spikes in short-abandoned calls during a specific IVR change tell you there’s a menu or messaging issue, not an agent problem.

Similarly, if one region shows higher post-call CSAT but identical scripts, you may have better carrier quality or routing there. Tie each critical metric to a part of the architecture: trunks, IVR, routing engine, CTI, CRM, WFM, AI. Your dashboards should help you debug the system, not just report what it did.

11. 90-Day Roadmap: Making Your Architecture Understandable and Fixable

Days 1–30: Map reality. Draw your current architecture from carrier to CRM in enough detail that an outsider could follow a single call end to end. Document every vendor, trunk, SBC, IVR, queue, and integration. Highlight “black boxes” where nobody is sure what happens. Compare this to best-practice blueprints from modern zero-downtime cloud call systems and note the biggest gaps.

Days 31–60: Fix brittle points. Prioritise changes that reduce risk and latency: clean up number plans, simplify IVR, remove unused queues, and standardise CTI behaviour. Put observability in place where you currently guess: detailed routing logs, call trace tools, IVR analytics, and quality dashboards. Align QA categories with architecture layers (e.g., “misroute” vs “agent error”).

Days 61–90: Modernise the backbone. Start migrating the most fragile components — often trunks, PBX, or legacy ACD — into a more flexible core, using approaches similar to structured PBX migration blueprints. Introduce multi-region, multi-carrier designs where volume and risk justify them. Make sure architecture, operations, and CX sit at the same table so every diagram has a clear owner and business purpose.